Undesigning AI

Infrastructure, worldbuilding, and the new roles of designers

This is a transcription of a presentation I gave at IUAV University in Venice, Italy in 2023. It has later been published in Italian in the book Usabilità e innovazione: Il ruolo chiave della ricerca per l’impresa a cura di Michele Sinico and re-edited here for the web.It’s August 2023 when I’m writing this and I wonder how this will sound in just 6 months considering the pace at which AI is progressing. But I’m not concerned with predicting the future here, I’m more interested in exploring the role of design in a changing technological landscape and I hope these ideas will be useful no matter which directions AI takes in the near future and will be applicable to other fields of design as well.

The design practice is inextricably connected with technology and its means of production and distribution, so it only makes sense that a transformational innovation like Generative AI is also challenging long-held design beliefs and practices.

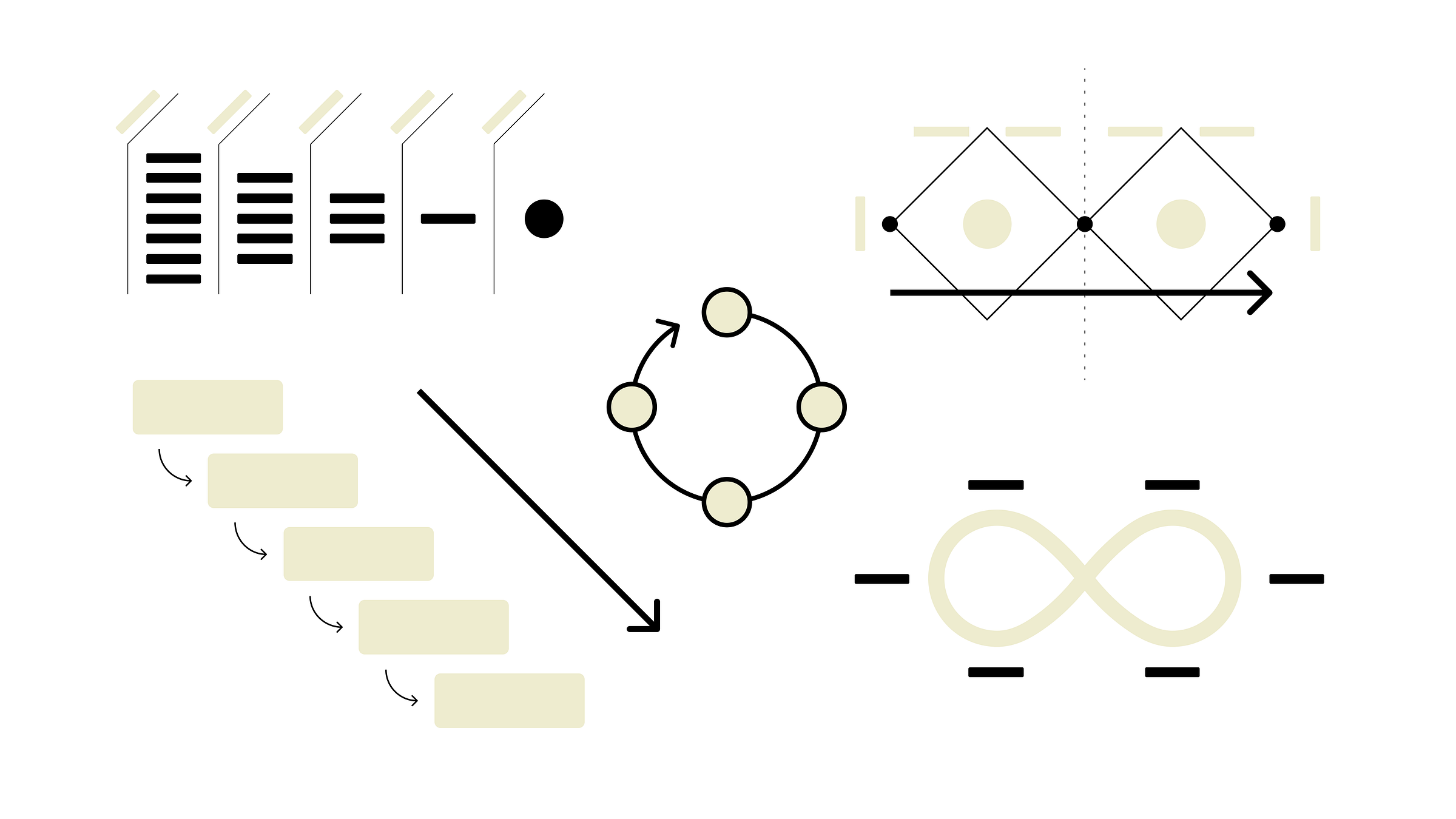

So let’s briefly touch on such traditional practices: open another tab and search for images associated with “product design process”. You will find variations of linear or circular processes where critical user journeys are defined, solutions are designed and tested, and eventually implemented as experiments in live products. If successful in improving the chosen metrics, these solutions are integrated into the current product until a new feature or problem arises, and the cycle repeats.

It is the manual labor of UX teams building or optimizing features in response to specific user needs, striving for the elusive product-market fit. It is what we teach at design schools, what we discuss at interviews, often showing images of post-its, paper sketches and diagrams (a side note: please don’t do it, they are part of the process but they don’t really tell much about the work that we don’t already know).

But it is also a process born from a specific technological milieu, one where web first and then mobile app development were a mostly manual labor of crafting singleton solutions to narrow problems.

Take another break and this time try searching on your phone or tablet’s app store for calendar apps. You will likely find plenty, each with a different take on the core narrow problem. One might help you automate reminder generation, one might be aimed at professionals, others might help families manage shared calendars across different platforms, and so it goes. Each app is a refactoring of the same narrow problem of remembering events and managing time, each one carries the specific point of view of the developers and designers, often a small team working independently or part of a larger corporation to provide the best possible solution for that specific user needs and compete with the others on features, ease of use, stability, usability, and usefulness.

Here you see the interconnectedness of the design practice with the underlying means of productions and distributions.

This approach is reflected in our design tools, which are often focused on the micro, the here and now and to a different extent in schools where designers are often taught to keep things simple, delightful, engaging, and fresh.

There is nothing inherently wrong with the product design process, at this point it is a well-honed approach and if implemented smartly it leads to fantastic results for both consumers and makers of technologies.

Complex AI systems might upend all of this, forcing us to look deeper and wider. And just a reminder that this is a “Yes, and” approach; I am not proposing to dismiss product design altogether, I am proposing instead to add other dimensions to it.

In 1977 Charles and Ray Eames produced a fantastic video titled Powers of Ten where they show a camera zooming through a logarithmic scale based on a factor of ten. Starting from a couple having a picnic in a park in Chicago, zooming out to show galaxies and then zooming all the way in to show atoms and quarks. This is still a fantastic film and a simple, visceral way to show the complexity and relativity provided by a different point of view.

It is also a useful metaphor for our design practices where traditional product design is akin to looking through the camera at 1X, focusing on the narrow and immediate of a specific combination of user needs and context: a couple having a picnic in a park in Chicago. Zoom out or zoom in and you suddenly find yourself designing in completely different contexts.

In the Eames film there is a particularly useful scene where the camera enters the skin of the hand of one of the actors. The camera zooms in and suddenly goes underneath a surface to explore the invisible. This motion is similar to how I think modern designers should approach working with complex technologies and systems because, as a rule of thumb I developed over the years, as the complexity of a technology increases the levers of good user experience become invisible, hidden under layers that were not traditionally the domain of designers.

Let me give you a concrete example. Imagine being a designer tasked with designing a traditional mailbox: most of the design decisions impacting the quality of user experience for people interacting with the mailbox would concern the shape, materials, constructions, affordances of the mailbox. Hide the inlet opening and people won’t find it, design it at the wrong angle and it will flood when it rains, and the list goes on. Get these superficial (meaning pertaining the physical appearance and functioning of the device) variables right and you will have a successful, usable product. Improve them iteratively and you will soon reach a great UX.

Imagine being tasked with designing a post office. The same superficial concerns would still apply: if spaces are not clearly marked and designed people might be confused or lost. Without the right affordances chaos would ensue as soon as the office gets busy. And yet in order to make the design successful you would also need to understand the postal service workflows, its procedures and regulations, which means that you would also need to consider and design for something that might not be immediately visible on the surface. A post office is a more complex piece of technology than a single mailbox.

Imagine then being a designer for a modern operating system, responsible for designing the platform that handles messages and notifications from hundreds of sources, human and otherwise, basically designing a complex world-wide network of digital mailboxes and postal offices, each with their own policies. Far from being a solved problem, it becomes obvious that focusing on the UI design of notifications and their controls is required but not sufficient to provide a good user experience. The most influential variable over how annoying, distracting, or useful and timely a notification could be can be found in the complex systems underneath: the collections of APIs, policies, and tools offered to developers, the spam and abuse filtering systems, the training of AI systems managing them, etc. All these variables are crucial to the product UX but oftentimes are removed from the daily practice of designers and I believe they should not.

So far we established how product design has been getting more complex and how designers should think and design at multiple scales, understanding both the surface and the underlying systems, thinking past 1X and expanding both to the macro and the micro. Let’s take a look now and how in particular Generative AI is making this need even more obvious and how designers could adapt.

As I said at the beginning, it is difficult to predict how things will evolve but so far the AI systems we are seeing growing in front of us are shaping to be incredibly versatile, excelling across a wide range of scenarios. And they can do all this with a simple, quite universal, albeit fuzzy, user interface: natural language.

Natural language is our latent space for making sense of the world and it is now also the interface/surface that can be applied to and become everything. What You See Is What You Get becomes What You Think Is What You Get. And it changes everything because once again means of production and distributions are put through a radical sea change driven by the generalist nature of LLMs.

This subverts three main tenets of traditional product design:

the continuous crafting of specific symbolic user interfaces

the focus on narrow product verticals and individual critical user journeys

the focus on deterministic/linear user journeys

Let me unfold this a little bit more. With AI, generic text-based applications can readily become canvases for memory, thought partnership, code generation, analyzing and aggregating data, developing new ideas. And yet, the surface is the same: it’s a chat, it’s textboxes, it’s a collection of buttons, it’s text morphed in different decorations.

We will still need UI design for these applications of course, but we might not need to have dozens of variations of similar UI patterns optimized for specific critical user journeys as today’s calendar apps.

We might desire more standardization, economy, and reusability of UI components because, as I described earlier, the crucial variables of the system making or breaking the user experiences, and ultimately deciding who wins the choice of customers, will be determined by aspects buried deep under the visible surface: the capability and consistency of a generative AI system, its trustworthiness, predictability, alignment, the speed and economy of execution, the ability to interface and operate different services and devices. And if these variables cannot be determined with traditional design approaches we will need to imagine new techniques and workflows to make sure designers can have visibility and influence over them, together with the other functions involved in their creation.

So, how should we adapt our design approach in this new landscape? Should we write and maintain lists of hundreds if not thousands of critical user journeys for generalist AIs and try to create design mocks of every possible variation of the interactions with these systems? It would be a daunting task and one that would anyway fail to capture all the possible variations and nuances of these systems.

I am exploring two ideas that I hope can help designers reframe their role and practices: infrastructure and worldbuilding as ways to think systematically and scale our design impact beyond the visible surface of products.

Infrastructures are the often hidden, less glamorous, systems that make a city, or a society, work. The mind obviously goes to bridges, railroads, and airports but also intangible things such as regulations and trade agreements are infrastructure.

If the concept of infrastructure is obvious and pervasive what is interesting is that thinking that goes beyond it. Whether you are an engineer planning a new subway station, a policy maker drafting a new regulation you have fundamentally two options ahead of you: focus on the immediate problem at hand and try to address it in the most fitting (or some might say overfitting) way or use the problem at hand as the starting point to consider solutions that can hopefully withstand the passing of time and changing of other contextual variable, thus not just building a solution but building infrastructure.

Designers are no strangers to infrastructures: typography, design systems, pictograms are all forms of infrastructure for the transportation of information.

Olympic games are an example that brings all these professionals together in showing the differences between the narrow and systemic approaches. Huge amounts of money have been traditionally spent by hosting cities for building, branding the games, only to generate a few years later abandoned buildings and forgotten designs. Luckily there are also positive examples of infrastructural approaches that equally contributed to great olympic games and had positive, lasting impacts on hosting cities and communities. I’m thinking for instance about Otl Aicher’s pictograms for the 1972 games or the deep infrastructural renovation that Barcelona went through for its 1992 games where the majority of the games budget was allocated to infrastructure renovation. The olympic games were the trigger to develop infrastructures, visual and literal, that long outlived the main event and generated greater impact in the following years.

Thinking of design as infrastructure means abstracting our work from the immediate problem at hand and training ourselves to think in ways that are more systemic and take a long-term approach.

I often think of UX/UI components as functions within a complex system signal flow. What does this component do? What is the input and what is the output? What does it encourage or discourage? It might seem strange at first but baring UI components from their appearances and thinking abstractly about how they function in the larger system often helps clarify how to design it.

In her seminal 2008 book Thinking in Systems: a Primer Donella H. Meadows defines a system as “elements, interconnections, and a function or purpose” and here I might say UX/UI components are one of the basic units of function designers can directly manipulate when dealing with simple or complex systems.

Regarding UX/UI components as infrastructure also means considering their interoperability, resilience, and maintainability. Contrary to how we might sometimes operate, newness and uniqueness are not necessarily desirable traits of designing infrastructures. Furthermore, viewing these components as infrastructure entails broadening the traditional definition of users to encompass multiple actors.

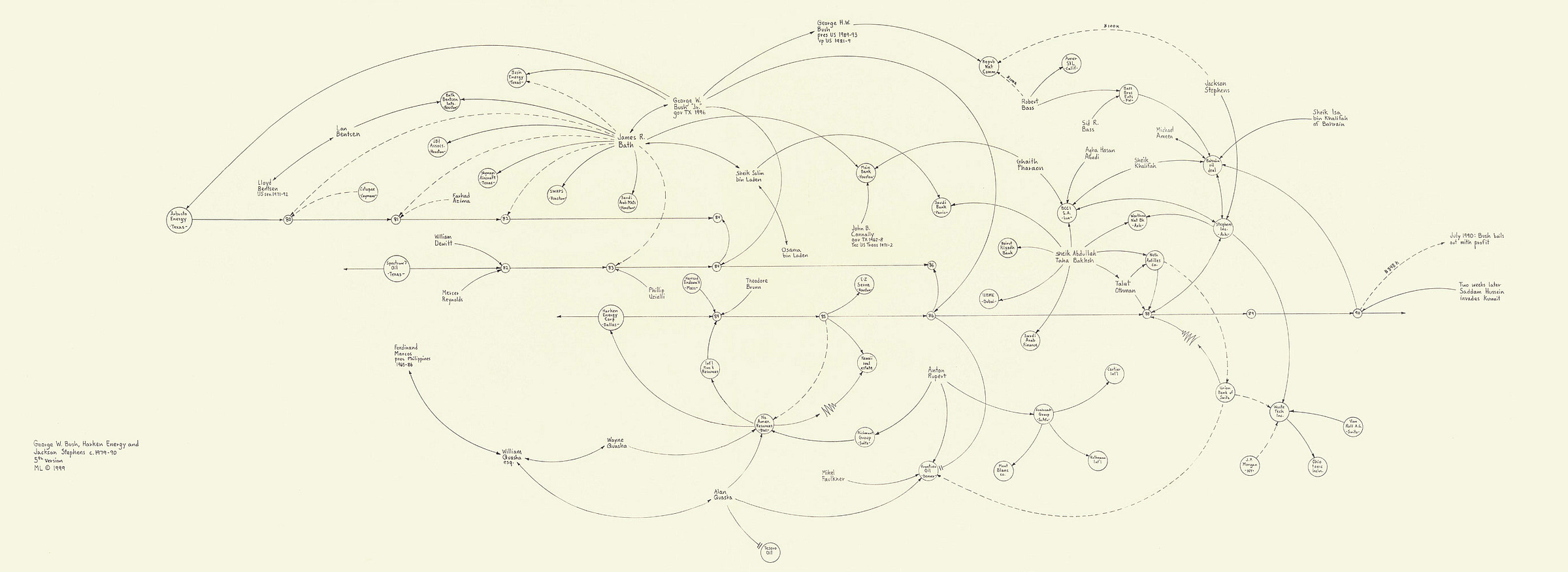

Bruno Latour's Actor/Network Theory has been influential in understanding these systems. When designing a component, we need to consider all actors and networks connected to it: end users, developers, administrators, regulators, wider communities, and even potential abusers of the system. This is not entirely new territory for designers. We have seen in the past good examples of user journey maps from Service Design practices. We have the tools to do this, but what needs to change is the mental model with which we use them. Mapping the actor network theory of a system means understanding roles, incentives, expectations and canonical user journeys of each of them. Designing UX/UI components means also actively choosing which paths/behaviors we want to incentivize or disincentive through the system and this means also designing both the visible and the invisible, which brings us to the second idea of this piece, worldbuilding.

The term has been traditionally associated with fictional entertainment across media, including novels, film, television, and games and it refers to the practice of developing a cohesive set of narrative infrastructures such as characters, geography, lore and laws that support the development of several stories by multiple creators and across different media. Star Wars, Game of Thrones, Final Fantasy or Super Mario are all massively successful examples of worldbuilding.

What is interesting to me in this concept is that the original world creators have to eventually pass the creative pen to others, letting go of the traditional authorial control and focusing instead on providing a solid foundation that can keep stories coherent. Worldbuilders create the sandbox and the building blocks with which others can build stories and experiences.

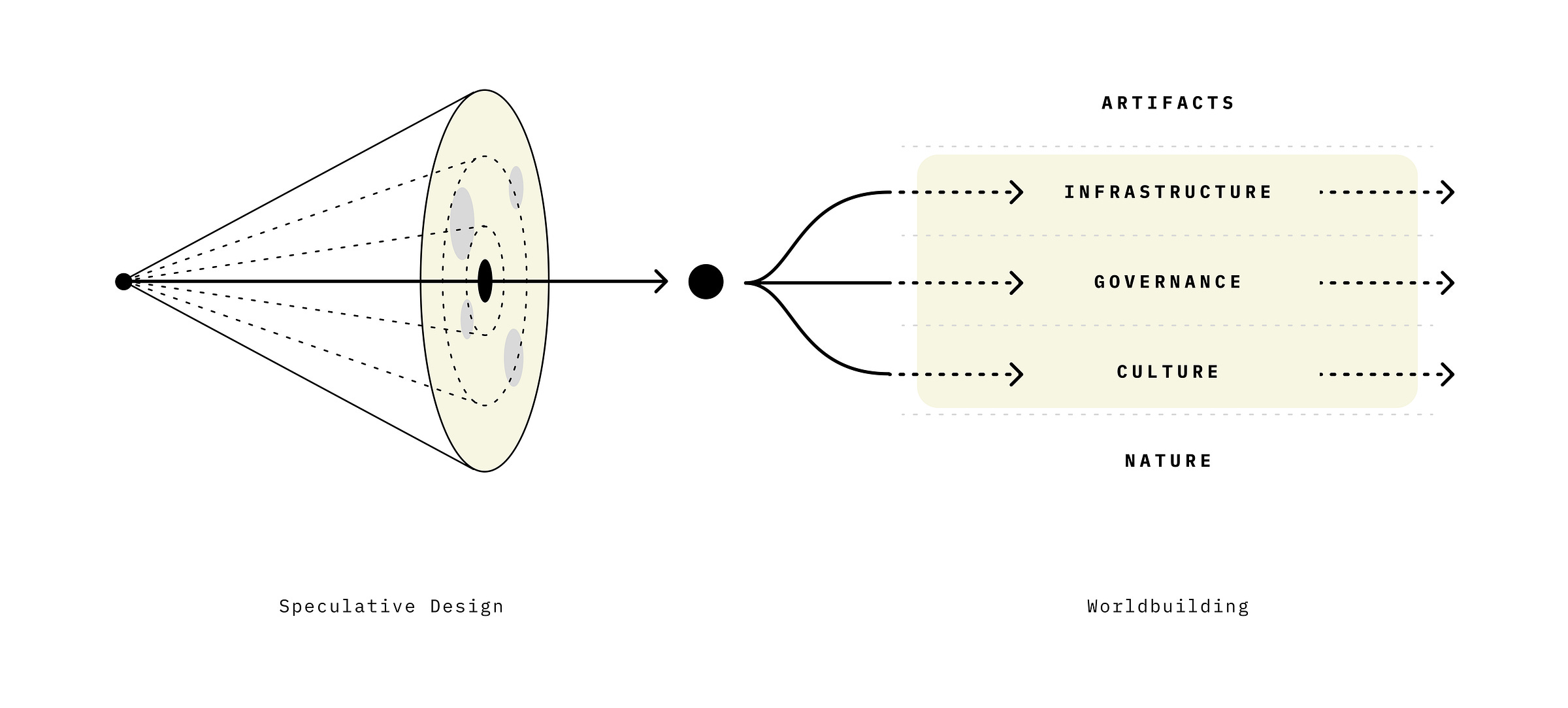

You might start to see some parallels with the infrastructural work of designers and you might also see similarities with well established practices of Speculative Design. Dunne and Raby are among my favorites with their critical and provocative work. Near Future Lab recently published a successful design fiction manual with clear examples on how to use speculative techniques to design artifacts from alternative and imagined futures. Another web search for Speculative Design will provide you with several renditions of the famous future cone diagram: the framework here is temporal and horizontal. The main verb are “Imagine”, followed by “visualize”, “embody”. We are asking designers to imagine the future through tangible artifacts such as books, magazines, and products as a way to visualize, critique and make sense of possible futures.

I think worldbuilding is a fitting companion because it adds a dimension of creation to the speculative explorations of what might/could/should happen in a given future and goes beyond traditional product design by putting an emphasis on the infrastructural elements needed to foster and steer building by many.

For designers to apply worldbuilding at an infrastructural level means considering the cultural, legal, and technological conditions needed for desirable futures to develop. It means adding more vertical dimensions to the temporal/horizontal speculative design framework.

I sketched this inspired by the concepts of Architectural Shearing Layers (buildings as composed of several layers of change) from Frank Duffy and the Pace Layers by Stewart Brand from the The Long Now Foundation.

Let's imagine a future where say 90% of content is synthetic, meaning being generated on demand from advanced generative AIs. What does it mean to be an artist, a musician in that world? Do copyright laws still make sense? If we don't have an experience of a shared cultural artifact what would we talk about? Or, in a completely different set up, let’s imagine a future where AIs are both individual and communal technologies, for instance helping an entire community thrive. How to balance individual and community wellbeing?

Through speculative design techniques we can critically examine these possible futures and with active worldbuilding we can start to define cultural, governance and technological infrastructures needed to develop them.

For example, what kind of platforms, APIs, and processes are needed to negotiate values among heterogeneous communities? How can we evolve the understanding and definition of human creativity and its contribution to the generative AI workflows? What kind of new technologies and legal framework can support it? These are abstract questions that can be explored in quite concrete terms… platform APIs can be prototyped, culture continuously evolve through discourse, legal frameworks can be negotiated and tested out, making worldbuilding a communal activity that can be used to activate and involve all the actors beyond the traditional design and engineering roles.

Evolving AI technologies are quickly going to change the way we design and build products, challenging some of the design processes (and roles). Thinking about our work as defining and building the infrastructures needed to support development of the worlds we want to inhabit, expanding our attention beyond the here and now and toward the macro, communal, long term seems to me something crucial at this juncture and something designers are well equipped to contribute to.

In this context worldbuilding is meant to be an act of collaborative negotiation, planning, and creation where designers get to extend the reach of their techniques beyond traditional product design.

References:

Brand, S. (1994). How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They're Built. New York (NY): Penguin

Bruno Latour (2007). Reassembling the Social. An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. OUP Oxford

The cover photo is a detailed of an experimental biogenic building material created for the 2023 Reset Materials: Towards Sustainable Architecture exhibition in Copenhagen, Denmark